Multitasking used to be cool. People thought it possible and aspired to it. Now, however, so-called productivity experts condemn multitasking. But the picture of multitasking they paint is woefully incomplete. The experts fail to acknowledge two ways in which multitasking is not only possible but very efficient.

What the Experts Get Right About Multitasking

Multitasking is the carrying out of multiple tasks or activities by the same person at the same time.

Article after article on multitasking argue that the most efficient way to complete two cognitively-demanding (i.e., thought-intensive) tasks is to focus solely on the first task until it is finished and then focus solely on the second task until it is finished.

For instance, imagine you have a business proposal to write that will take one hour if you work on it uninterruptedly. And imagine you have 60 emails to process that will also take one hour if you work on them uninterruptedly. By focusing exclusively on the proposal and then exclusively on email, you can complete all the work in 2 hours.

If, however, you try to multitask, it will take you longer—up to 40% longer—to finish the proposal and process all of the email. Why?

It will take longer because 98% of us can’t do two such tasks simultaneously. The best we can do is switch back and forth (rapidly or otherwise) between the proposal and email. Every switch wastes time. That time adds up. In the end, it takes us more than 2 hours to complete the two tasks.

I completely agree with the experts that attempting to multitask between two such activities is very inefficient.

Key Distinction: There are Different Types of Tasks

But not all tasks are like writing a business proposal or checking email—a point the experts miss or else gloss over. But it’s an important point. Multitasking may be possible with some combinations of tasks. Let’s see.

There are three types of tasks worth considering:

- Dense-Thought Tasks. Writing a business proposal and replying to email are examples of these types of tasks. They demand intense thought. What’s more, they demand constant concentration. They are “dense” in the sense that they have no room for the insertion of another task into them. Every interruption of such a dense task increases the time required for its completion. These are the types of tasks that experts on multitasking fixate on. But they are not the only type of task.

- Loose-Thought Tasks. Like “dense-thought” tasks, “loose-thought” tasks also demand intense thought. But they don’t require constant concentration. They require our full attention but only for short bursts of time, which can be punctuated by short bursts devoted to concentrating on something else. An example of an activity that is cognitively-demanding but “loose” is watching a baseball game on TV. You must pay attention thousands of times during the game to appreciate it. But those thousands of moments of concentration on the game can be punctuated by thousands of moments of concentrating on something else. Between pitches or certainly during commercials, for instance, you could focus briefly on something else such as checking scores from other games or folding laundry.

- Habitual Tasks. Habitual tasks are activities you can perform with little to no thought. They may be complex, but because they are habits, they require very little thought. Examples include eating, walking, and showering.

The Multitasking Matrix

Having distinguished between those different types of tasks, we can now ask whether certain combinations of tasks can lead to greater efficiency. That is, we can examine whether multitasking is possible and perhaps even beneficial in some cases.

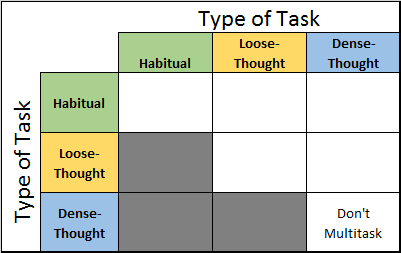

I’ve laid out the possible combinations of tasks in the following grid. Let’s call it the “Multitasking Matrix.” 🙂

I’ll fill the grid in as we go. All we know at this point is that you shouldn’t attempt to do two cognitively demanding, dense tasks at the same time. Attempting to do so decreases efficiency. That’s the point the experts repeatedly make.

What the Experts Miss About Multitasking

But the experts completely miss two ways in which multitasking is not only possible but extremely efficient.

1. Multitasking Works When At least One of the Two Tasks is Habitual

It is entirely possible to do two tasks simultaneously when at least one of them is habitual. And doing so drastically improves efficiency. Consider these possibilities:

Two Habitual Tasks

Have you ever walked to a meeting while taking a drink of water? Combining two such habitual activities is literally a no-brainer. Doing them at the same time is twice as efficient as doing them one after the other.

One Habitual Task and One Loose-Thought Task

Or imagine walking on the treadmill while watching a baseball game on TV. That combination of habitual activity with loose-thought activity is also twice as efficient.

One Habitual Task and One Dense-Thought Task

Lastly, imagine going for a walk while pondering an issue. Many authors and philosophers swear by this practice. Friedrich Nietzsche, for instance, said, “It is only ideas gained from walking that have any worth.” The combination of a habitual activity and a dense-thought activity is not only possible but often twice as efficient as doing them separately.

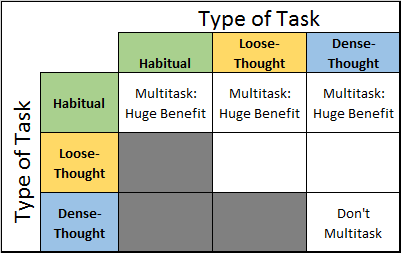

I therefore conclude that whenever at least one of the two activities in question is habitual, multitasking is not only possible but extremely beneficial from the standpoint of efficiency. Here is the Multitasking Matrix, updated to reflect that conclusion:

2. Multitasking Works When At least One of the Two Tasks is a Loose-Thought Task

But let’s return to the harder case: the case where both tasks are cognitively-demanding. Here, too, I argue that multitasking is possible provided that at least one of the cognitively-demanding tasks is “loose.”

Two Loose-Thought Tasks

Consider this example. You and your significant other have a conversation while driving to a new restaurant 30 minutes away. Both driving to a new location and conversing are cognitively-demanding tasks. But, like watching baseball on TV, I’d argue they are cognitively-demanding tasks of the “loose” variety.

During the 30-minute drive, you quickly switch back and forth many times (probably thousands of times) between focusing on the conversation and focusing on the drive. You may even have to interrupt the conversation at some point to double-check an upcoming turn.

Let’s say the interruptions to the conversation are such that you could have had the same conversation in 25 minutes were you not driving.

If you drove without talking and then had the conversation after completing the drive, it would take you 55 minutes (30+25) to complete both activities. By driving and talking at the same time, however, you complete 55 minutes of cognitively-demanding activity in 30 minutes. In this example, you increase your efficiency by 83% (25/30) through multitasking.

One Loose-Thought Task and One Dense-Thought Task

Finally, take, for instance, replying to email (dense-thought) while watching a baseball game (loose-thought). Imagine you have so much email that it would take you 3 hours to process it if you focused solely on it.

By switching back and forth between email and baseball during a 3-hour game, you certainly won’t get all of your email done. And you won’t catch absolutely everything in the game that you would have if you were glued to the TV.

Let’s say you get one-third of the email done. That amounts to 1 hour of activity. And let’s say you have 80% awareness of everything that goes on in the 3-hour baseball game. That’s equivalent to 2.4 hours of baseball watching (80% x 3).

In that case, you completed 3.4 hours of activity (2.4 hours of baseball-watching and 1 hour of email) in 3 hours. That’s a 13% increase in efficiency.

Don’t get me wrong. There are plenty of good reasons not to work while relaxing. Our alleged inability to do so effectively, however, just isn’t one of them.

Conclusion

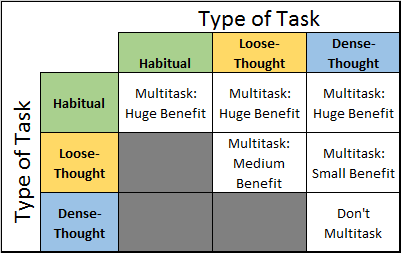

Based on the forgoing considerations, here is the completed Multitasking Matrix:

As you can see, the expert advice on the possibility and efficiency of multitasking is only right in one instance: namely, when both tasks are thought-intensive and dense.

Those are some of the most important types of activities people can undertake, so they are well worth safeguarding, as I will argue in a future post. But the path to safeguarding those activities should not be to deny the possibility of multitasking.

For many types of activity, multitasking is both possible and a meaningful boost to efficiency.

So the next time you walk across the street, don’t hesitate to check for traffic as well. You can do both at the same time, and you might be glad you did.

Question: In what ways have you found multitasking to be efficient? In what ways inefficient? You can leave a comment by clicking here.

If you liked this post, why not join the 5,000+ subscribers who receive blog updates on how to have more time and money for what matters most? Sign up here.